Why Being Vulnerable at Work Can Be Your Biggest Advantage, According to Brené Brown

Brené Brown—research professor, bestselling author, and star of one of the most popular TED Talks of all time—was in an awkward spot. Speaking to 150 hedge fund managers in London, she was five minutes into her presentation on vulnerability and courage when one bold Brit raised his hand.

“I don’t know why you’re here,” he said. Ouch.

It was a mandatory meeting, and the hand-raiser clearly wasn’t alone in his frustration. “We’re in a highly compliance-driven industry,” he said, “vulnerability simply isn’t an option for us.”

Ah-ha. “What’s more vulnerable,” Brené asked, “than standing up in front of a group of people who you work with and saying, ‘this is not the right thing to do’? What’s more courageous than making an ethical decision when all your peers are going the other way?” Now they understood.

And courage and vulnerability are as critical for hedge fund managers as they are for HR professionals. Every business can benefit from braver leaders and a more courageous company culture. And talent professionals play a key role in shaping that culture, finding courageous candidates, and developing courage in others and themselves.

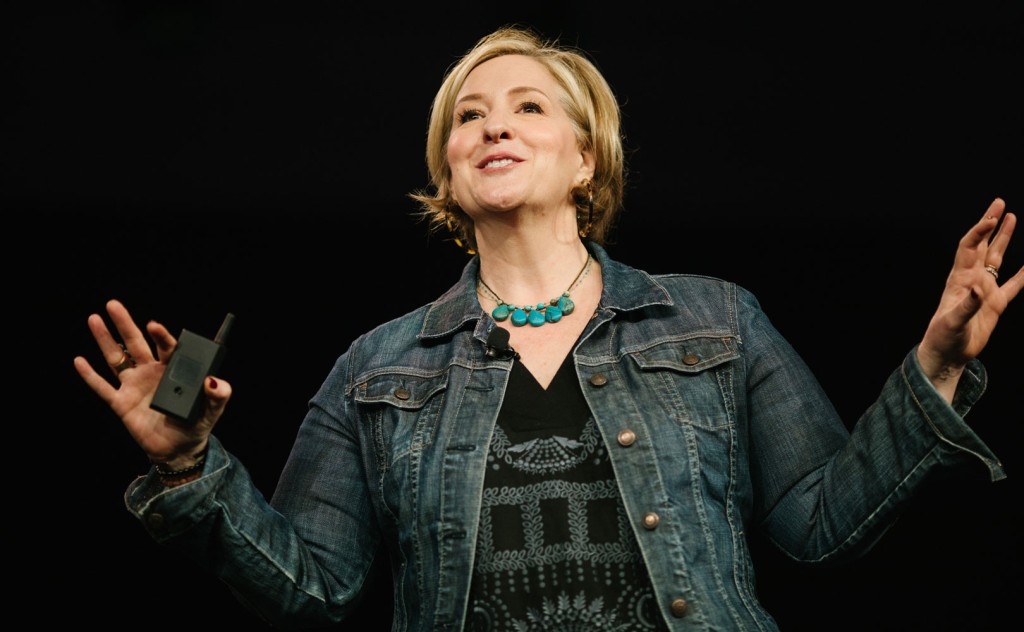

At Talent Connect 2017 in Nashville, Brené broke down courage into four foundational skillsets—the four pillars of courage—and told recruiters and HR professionals how to measure and cultivate these key skills.

1. Vulnerability: the willingness to show up and be seen, despite uncertain outcomes

Brené was making conversation with a stranger when he asked what she did. “I study vulnerability and courage,” she said.

“Oh, so you work on both ends of the spectrum? Those are opposites, right?” he asked.

“No,” she said, “they’re absolutely not opposites—they're the same thing.”

It’s a common misconception. Society has taught us that vulnerability is synonymous with weakness—but Brené says that it’s just the opposite. Vulnerability is the willingness to show up and be seen by others in the face of uncertain outcomes. There’s not a single act of courage that doesn’t involve vulnerability.

That’s as true at work as it is in our personal lives. “Vulnerability is the birthplace of innovation, creativity, and change,” Brené says.You can’t really innovate without risk or uncertainty. “If you’ve created a work culture where vulnerability isn’t okay, you’ve also created a culture where innovation and creativity aren’t okay.”

Vulnerability and courage allow you to have difficult, uncomfortable conversations with colleagues—and almost any company culture could improve by having more difficult discussions.

Brené shared an uncomfortable conversation she recently had with one of her employees. “Your passion is contagious,” the employee said. “But sometimes your emotional intensity creates a wind tunnel that’s hard to stand in and impossible to respond to. It shuts me down.”

It was hard for Brené to hear that—but it was ultimately helpful. Every leader can benefit from having hard, vulnerable conversations like that.

All transformational leaders had this one thing in common, according to Brené’s research. “The capacity for difficult conversations,” she said. “Imagine a leader who could pull a team together and say, ‘I’m not good at this, but I feel like there’s unspoken stuff happening around gender and race, and I want to talk about it.’” Vulnerability is critical for leaders and employees alike.

When hiring for your company, you should look for candidates who exhibit a willingness to be vulnerable—whether that’s owning up to past mistakes in an interview, sharing potentially embarrassing hobbies, taking risks, or embracing hard conversations.

2. Trust: the courage to trust others and the integrity to be worthy of trust from others

Everyone can agree that trust is key part of a collaborative workspace, but it’s such a big concept, it can be hard to put your finger on exactly what it means. To help people get a sense of the meaning of trust, Brené breaks it down into seven component parts represented by the acronym BRAVING—since trust is braving connection with someone else.

These are the seven behavioral traits to look for in candidates and coworkers who exemplify trust and trustworthiness:

- Boundaries: you set your own boundaries and respect those of others.

- Reliability: you have to do what you say you’ll do—that means not overpromising at work, being clear about limitations, and delivering on commitments.

- Accountability: you own up to your mistakes and fix them.

- Vault: you don’t share confidential information that’s not yours to share.

- Integrity: you do what’s right instead of what’s easy, and you practice your values instead of just professing them.

- Non-judgment: you can answer requests for help without judging those who ask, and you can ask for help yourself.

- Generosity: you extend the benefit of the doubt to people’s intentions, words, and behaviors.

Breaking down trust into its component parts makes it easier to talk about trust at work. Imagine an employee is always turning things in late, and you can’t trust them to deliver on time. “Instead of saying, ‘we have trust issues,’ you can say ‘we have reliability issues,’” Brené suggests. Now you’ve made it more specific, and you can constructively work on a solution.

Brené also explained how non-judgment is particularly important at work—not judging others or yourself, especially when you need help. She found that asking for help was the #1 trust-building behavior in a survey of over 1,000 leaders. “Would you delegate an important project to someone who’d never ask for help if things go underwater?” Brene asked. If you create a work culture that doesn’t tolerate vulnerability, people will never ask for help.

Everyone struggles with trust in a professional context—but by breaking it down into BRAVING skills, you can practice developing trust in yourself and identify trust in candidates and colleagues.

3. Rising skills: the resilience to get back up when you fail

If you’re going to risk being brave, courageous, and vulnerable—if you’re going to show up and be seen—“you’re going to get your ass kicked,” says Brené. It’s a natural consequence of courage, and it’s why it’s so difficult. But it’s just as important to rise and pick yourself up when you’re inevitably knocked down.

Brené shared a quote she found from Theodore Roosevelt that she says “changed her life” and summed up everything she’s learned about vulnerability in 15 years of research. Sometimes called the “man in the arena” speech, the quote reads:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; [...] who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly.

For Brené, that quote shows the power and nobility of being vulnerable. You’re going to get dirty and probably hurt, but at least you’re in the arena doing it.

She also finds the quote incredibly freeing, because it helped her ignore all the critics in the cheap seats. “If you’re not in the arena and also getting your ass kicked on occasion,” Brene says, “I’m not interested in your feedback about my work—period.”

Rising skills are essential to weather the hardships that come with courage. Talent professionals should look for people who have tried and failed and tried again—and they should develop that resilience within themselves, too.

4. Clarity of values: the thing that reminds you why you tried in the first place

Almost all businesses have some sort of company values, but far fewer actually live them. “One of the biggest problems I see at organizations is that you haven’t operationalized your values,” Brene says. That means translating your values into specific behaviors that are observable and measurable.

“If you don’t translate your values into behaviors, your values are just like those stupid inspirational posters from the ‘80s,” Brené says.

Our values define us at the deepest levels—they’re what we call on when we get knocked down, and they’re what gives us the strength to try again. Brené says that she’s found almost universally that you can’t “live into” your values without vulnerability and courage.

It’s easy to think that courage and vulnerability only apply to our personal development and personal relationships—not the professional self that we bring to work. Brené shows us that these values are just as important in the workplace. A more courageous culture means colleagues can have discussions that are uncomfortable yet crucial.

It means coworkers can trust, confide, and respect each other more. It means your team can learn from failures instead of getting discouraged. And it means crystallizing your company’s values so candidates and current employees see that they can bring their whole selves to the workplace.

To receive blog posts like this one straight in your inbox, subscribe to the blog newsletter.

Topics: Company culture Talent Connect

Related articles